As an autistic writer, a project never really fizzles out…

Amy Vickers joins Cave of the Heart and answers 6 questions on self-trust

Welcome to Cave of the Heart, an interview series where writers trust-fall into the depths of inner-knowing, creativity, and the craft of writing. Are you ready to get curious about the cultivation of self-trust, give a warm nod to our child selves, and celebrate inspiration in all forms? Come with us into the cave of the heart.

is looking to make a connection. Her writing as an autistic woman is sincere and earnest, and she works hard on every piece. She is the author of a Substack newsletter called The Intentional Hulk, where she mostly writes essays about her life. She also writes short stories and has written a memoir (hopefully, upcoming).Describe the setting where you’re answering these questions.

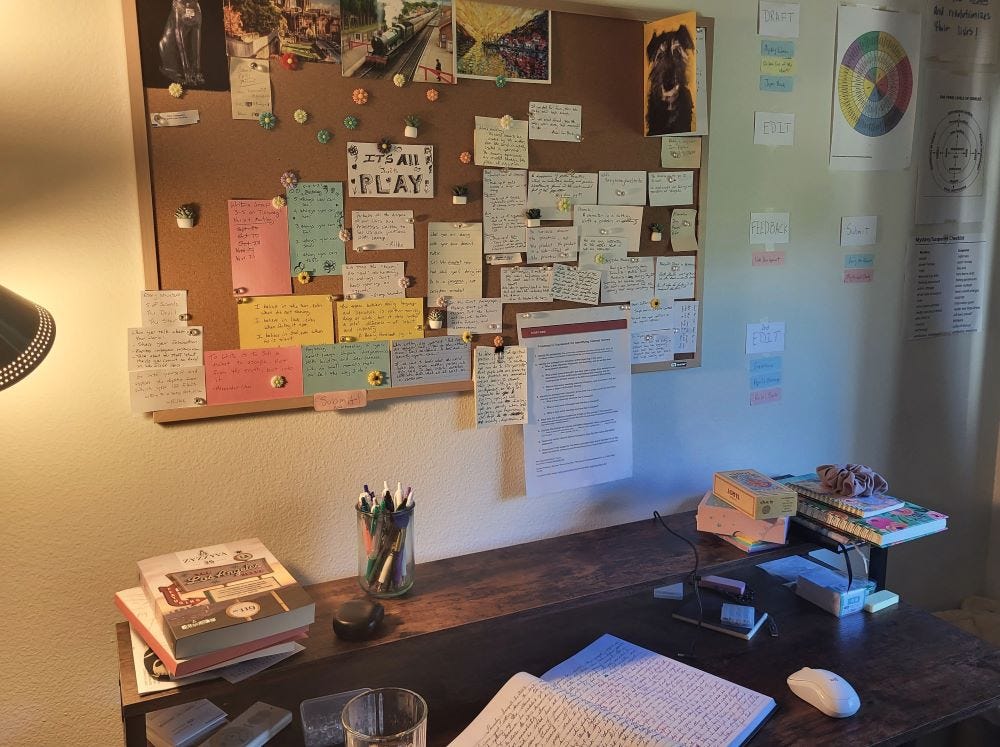

Every morning, I sit down at my desk, write in my journal, and do a tarot reading with my Dreaming Cat tarot deck. It’s an ordinary brown desk. The important part: It sits in front of a cork board covered with notes, quotes, and postcards that comfort and inspire me. Slightly secondary, but also important: I have a lamp that changes angles and colors and a window I can open or close. Outside is green, green, green because I have palms, evergreens, and fruiting trees out there, and sun, sun, sun because I live in Southern California. On most days, I somehow manage to stay inside and write. This is partially because there’s a cat on my lap.

Childhood

Q: Were you a chatterbox as a child, or were you quiet or something else entirely? When you spoke up or expressed a preference, what sort of response did you get?

I was so shy that I didn’t speak a word to anyone outside my family until preschool. My mom walked me to school that day. The lawn sprinklers were coughing and hissing, so it must’ve been early morning. The teacher offered me something to come out from behind my mom’s legs. There were words in my head, but I couldn’t release them.

The last I saw of my mom, she was silhouetted against a rectangle of sun as she ran out the door. She didn’t abandon me there. She’d be back later, but I had to take my seat among the other children, whom I assumed were all orphans because I hadn’t seen their parents. The teacher asked questions and the kids shouted answers. Finally, my words started coming out, too.

During playtime, I chose to be on my own. By the time I’d decided to engage with the other kids, they’d already created their own groups and routines, and I didn’t know how to enter into that space.

I somehow intuited (sometimes correctly, sometimes incorrectly) that no one else had any desire to meet my needs, so I always hid them the best I could.

Influences

Q: If you had to choose one person from your past that most influenced who you are today, who would that be and why? This can be a person from history, an animal, a fictitious character in a book, TV or movie.

When I was a kid, Anne from Anne of Green Gables was my biggest influence. Like her, I had a rich inner fantasy world, and it caused me similar problems. L. M. Montgomery wrote Anne with such tenderness that it’s impossible not to cherish Anne for who she is, which taught me that someone like me can have value.

As an adult, my main creative influence has been

. I was in my late 20s and going through a divorce when Eat, Pray, Love came out. Like her, I’d been killing myself to please an unpleasable world and hoping it would result in some sort of reward. Once again, I was drawn to someone who found answers by looking inward rather than outward.Several years ago, she did a podcast called Magic Lessons. That, and her book, Big Magic, were the life-lines I needed to keep going when I was at my most vulnerable as a writer.

It seems like every time she puts something out into the world, it’s exactly what I need at the moment. Like the newsletter she’s doing now, Letters from Love, always calms me down when I’m wigging out about something. I’ve been using this practice ever since she described it in Eat, Pray, Love, but not consistently. Her weekly newsletter reminds me that I always have a little bit of enchantment in my back pocket for emergencies.

Her work also got me hooked on memoirs, especially by women. It’s my way of hanging out with someone knowledgeable, wise, or just plain entertaining. I usually end up having great affection for the authors by the end.

This year, I’ve read memoirs by Alexander Chee, Lauren Graham, Prince Harry, Ashley C. Ford, Elizabeth Alexander, Katherine May, and Rachel DeLoache Williams. If you stretch the definition of “memoir,” I’ve also read Lili Anolik and Eve Babitz.

My favorite fiction writer is Donna Tartt. Her work is so rich, intricate, atmospheric, and a little creepy. It reminds me of a painting by Hieronymus Bosch. She shows a lot of courage by writing with detail and complexity in a world that demands minimalistic prose and messages that hit us over the head. I wish I could write like her, but my mind just doesn’t work like that.

I just recently discovered Denis Johnson, so we’ll see how that goes. I’ve also always loved F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Creative Spark

What was the last creative spark that you were really excited about, but it ultimately fizzled out? What do you do when something doesn’t come to life like you’d imagined?

It depends on where you draw the “fizzle” line. I’m a perfectionist, so I’ll rework things until I’ve memorized them. I don’t consider it a fizzle to move onto something else. My creative life is like a long road trip. I might see mountains, cities, beach sunsets, etc., but my momentary focus on one thing doesn’t diminish my appreciation for the others. Sometimes, I go back to projects years later. So, I guess that, for me, there’s no such thing as a true fizzle.

Of course, there are disappointments. I “give up” all the time, but the thing is, I keep waking up the next morning wanting to write. And, just like on a road trip, there’s nothing to do but get out of bed and keep going.

Writing Process

What does your writing life look like today, and can you compare/contrast it to 10 years ago?

I decided to take a sincere crack at writing about ten years ago, and I’ve changed my approach in several ways since then.

When I started, I was very focused on the end result and considered the practice of writing to be a necessary evil to get to the product. If I still worked that way, I wouldn’t be writing anymore. Now, I take the practice very seriously, and I try not to take the end result very seriously at all.

I used to worry a lot about how the world would receive what I wrote, but, so far, the world only begrudgingly accepts a few things from me, then it rolls its eyes and moves on. So, now, I worry more about whether something will be read at all, let alone how it’ll be received.

I started out a lot more confident in my writing, and, after ten years of dedicated practice, I’m not sure I’m any better at it. I know that sounds impossible, but I’ve let a lot of people jerk me around and give me bad advice. Most of the bad advice had to do with fixing what was wrong with my writing rather than nurturing what was right with it.

These people didn’t have bad intentions. In many cases, I never met them. I just read their books on how to be a good writer. In critique settings, most people did their best with what they saw on the page.

We all live in a paradigm that tells us that things become perfect when the flaws have been eliminated. The internet allows us to trade so many “tips and tricks” and style advice that we’ve whittled ourselves down to a few homogenous voices. The irony is that the more homogenous we are, the more vulnerable we are to AI.

I’ve applied all the writing advice and have literally edited myself down to a blank page. It felt like a constant game of Twister. I’d have one hand on red, put my foot on green, and keep going like that. My voice just got so awkward and self-conscious that it couldn’t hold itself up anymore.

Now, I think the “problems” in a piece are inextricably linked to whatever makes it unique and exciting. When I work on a piece, I think far less about pleasing my potential readers and far more about identifying whatever is essential to it and bringing that forth. It’s my way of communing with whatever’s out there to commune with.

recently wrote about how the “problems” of a piece are inextricably linked to the advantages of it in a recent Office Hours post. I got that idea from him. Well, it was an idea I had, but he confirmed it.Resources

What’s your favorite quote on writing?

I have two, right now:

“To write is to sell a ticket to escape, not from the truth, but into it.” – Alexander Chee

“Perhaps all the dragons of our lives are princesses waiting to see us act just once with courage.” – Rainer Maria Rilke

Neurodiversity

Did being diagnosed neurodivergent affect how you see or interact with your writing life?

It was a relief to finally have an explanation for why I am the way I am when I was first diagnosed with autism, but it really shook my faith in my own judgment.

I’d only started trusting myself about five years before, and the trust I’d been building in myself was rooted in a faith that I was fundamentally the same as everyone else. I’d dismissed everything that’d previously made me feel alien, like that situation where I didn’t speak to non-family until I got to preschool.

My environment growing up was extremely unconventional, so I believed my differences were the result of poor socialization and trauma, which I saw as fixable, but my diagnosis undermined all of that.

The most important thing a writer needs to develop is taste, so we can edit our own work. This is why I read as much as I can, but now, I think about all those words going through my “autism filter.” I’m afraid I’ll never fully understand the neurotypical perspective and, therefore, never develop the ability to write things that really speak to people.

On the other hand, I read a book by Devon Price called Unmasking Autism, where he writes, “Neuroscientists have observed that Autistic brains continue to develop in areas associated with social skills for far longer than neurotypical brains are believed to. One study, [found that] by age thirty no differences between non-Autistics and Autistic people were evident.”

Price theorizes that we teach ourselves to be consciously aware of things that are subconscious for neurotypicals. This aligns with my experience. I’ve learned to be powerfully observant just to have the same foothold as everyone else, and adept observation is at the core of good writing.

So, maybe I still see myself on a path toward self trust, like I was before my diagnosis, but the map has changed. I was only diagnosed a year ago, so I’m still figuring it out.

Also, now that I’m aware of autism, I see evidence of it everywhere. I suspect that many of my favorite writers were autistic. Of course, many are dead now, so there’s no way to know for sure, but it gives me hope.

Next up

A conversation with my editor about newsletter first impressions, more inspiring Cave of the Heart questionnaires, and a vulnerable essay about surviving the pandemic with dissociative identity disorder. Subscribe to follow along.

Join Amy in the Comments

Reflecting on Amy's journey with neurodiversity and her connection to characters like Anne from Anne of Green Gables, how has your own identity or experiences influenced the way you relate to certain characters or stories? Share an example of a character or story that resonated with you deeply and why.

Considering Amy’s evolving approach to writing—from focusing on the end result to embracing the practice itself–how has your approach to a passion or skill changed over time? Share your experiences of how your perspective shifted and the impact it had on you.

Reflecting on the craft of writing and the path to self-trust, what piece of writing, whether yours or someone else's, has recently touched you deeply or helped you see the world in a different light?